Before there was sunscreen, before there were inexpensive sunglasses: ladies and gentlemen, there were hats, and for women (and possibly little boys) there were sun bonnets. This one has a patent date of 1899; I date it a few years later. The Women's Institute (WI) book Aprons and Caps has a good section on making sunbonnets and sun hats. Chambray and coarse torchon lace were recommended for everyday bonnets, with sheer white cotton for fancy bonnets ("chust for nice" as the Pennsylvania Germans say.)

Remember that at the beginning of the 20th century the percentage of Americans living on farms was much higher than it is today, so this would have been a good saleable pattern and not a curiosity or costume piece.

The indication that this sun-bonnet was for ladies, misses, girls, or children makes me wonder if sun bonnets were sometimes worn by very little boys. If you leave off the lace there isn't anything horribly girly about a blue chambray sun-bonnet, and the image of a little guy in overalls and a sun-bonnet is rather appealing.

Sun-bonnet patterns continued to be available into the 1960's; I have one from this period that was sold on its own and another one that was included with an apron pattern. It was possibly one of these that I saw being worn by an older woman last week when we were in the grip of a ferocious heat wave. She was very fair skinned, nicely dressed, and wearing what I suspect was her gardening bonnet, now faded, made up in a pretty brown and white Liberty-like print with ribbon ties.

March 2009 update: I had a few hours to fill recently and decided to make up this bonnet. Using this Ladies' Home Journal cover from May, 1908 for inspiration, I unearthed some blue and white gingham I had bought some time back in the last century.

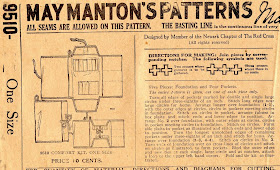

Here are the directions provided on the pattern envelope.

That's it, you're on your own. Good luck. Fortunately, the WI's Aprons and Caps booklet includes excellent instructions on sunbonnet construction. Here is their bonnet gal:

WI notes that "dress-up" bonnets can be made of sheer white muslin or dotted swiss. One imagines that these ladies in 1902 Florida put on their beautifully starched, white, dress-up bonnets just to have their photograph taken. This image from

Shorpy:

The Butterick pattern calls for cape net for the brim interlining. My Fairchild's

Dictionary of Textiles defines cape net as "Stiff cotton net. Synonym for rice net, which see." I dutifully thumbed ahead to Rice Net which I learned is "A term sometimes used for buckram." Since I haven't seen my stash of buckram in at least the last two moves, I decided to follow the WI instructions for making interlining by heavily starching together multiple layers of thin cotton fabric. WI recommends cutting up the backs of worn mens' shirts to use.

Instead I used some good quality unbleached muslin I had on hand. I mixed up a little heavy starch solution and gave the muslin a good soaking.

Then I carefully smoothed out the two pieces, one on top of the other, and ironed until dry. Here's the finished interlining piece draped across the back of chair so that you can see the stiffness. I'd say it's about as stiff as heavyweight non-woven interfacing but nowhere near as stiff as buckram or bonnet board. It's very nice to work with.

Here are the bonnet pieces cut from the gingham.

And here is the finished product.

On the Butterick pattern there is an optional frill around the brim, made from a plain length of fabric that is gathered. I didn't do the frill around the brim, making my bonnet somewhat on the severe side. In the WI example, the brim frill is shaped - deeper at the sides, narrower at the top of the brim. I may have to make another bonnet with a frill, just so I can have an excuse to use the gathering foot for my sewing machine.

The Butterick pattern indicates the line on the crown/curtain at which a quarter inch tuck is made to form a casing, but there are no instructions on making an opening in the casing or attaching the cords. I worked an eyelet in the center of the tuck casing, and threaded in some very narrow grosgrain I found in my ribbons box.

Here's the inside of the bonnet before the crown/curtain has been gathered. You can see that I bound the raw edge of the brim/crown seam.

The WI instructions take a very different approach to constructing the bonnet. The brim and crown edges are bound separately and then snap fasteners attached to both so that the brim and the crown are snapped together.

The reasoning here is that the bonnet can be taken apart for laundering; the brim and the crown will both go through the ringer flat and can be easily ironed. I've seen a fair number of sunbonnets through the years and I've never seen this type of construction. I think I'd worry about the bonnet flying apart in a stiff breeze. And I don't much care for sewing on snap fasteners.

Here's the inside of the bonnet after I've pulled up the cords. You can see how the brim has been pulled in. The WI book states that it's not tidy to leave these cords hanging, and recommends making a small bag, about 2 inches square, and sewing this just below the casing so that the cords can be tucked into the bag. Well, maybe.

Here's the outside of the bonnet after the cords have been pulled up.

Now here's the outside of the bonnet with the back bow tied.

I'm not certain if the back bow is functional or not, since it doesn't seem to draw the curtain in any further. I wear my hair in a simple bun dressed low, and the bow does seem to rest against the bottom of my bun, making the bonnet feel a bit more stable.

Here's the bonnet on, with the strings left hanging. The bonnet feels remarkably stable, not at all as though it's trying to tip back off my head.

Here's the bonnet with the strings tied. You can see how the shape of the brim has changed.

Here's a side view.

And here is a back view. I guess those white cords do look a bit untidy. It's interesting that the back bow is barely visible.

So, now I know what it's like to make the sunbonnet, and what it's like to wear it in the safety of my own home. The next test will be to wear it outside on a sunny day to determine how useful it really is.

_(cropped)%20(1).jpg)

.jpg)