1915-1916. This is the first pattern I've seen for a front buttoned work apron, making this closer to the smocks that we see in the 1920's than to the back-closing work aprons we've seen up until now.

You can glean some interesting details about May Manton (the nom de plume of Jessie Swirles Bladworth) in Women's Periodicals in the United States. May Manton patterns were a sort of spin-off of McCall patterns. Presumably all the involved parties thought that there was room in the home sewing market for yet another pattern company. To my eye, May Manton patterns don't have quite the polish of McCall patterns, so perhaps they were aimed at a different sector.

The newspaper advertisement for this pattern provides some interesting details. The pattern is being marketed to both the "housewife and artist."

Rome (New York) Daily Sentinel, Tuesday, November 2, 1915, page 9

By 1915 most sewing patterns included the seam allowances, but the May Manton pattern notes that it also "gives the true basting line." May Manton apparently believed that providing the basting line (the eventual seam line) on their patterns was a worthwhile feature, which they note on both the pattern envelope and in their advertising.

Sewing instruction manuals at this time always include instructions for the different types of basting stitches and guidance on when they should be used.

Clothing for Women, Selection, Design, Construction, 1916, page 208

Whether hand sewing or machining, hand-basting has some advantages to pin basting. It's less liable to distort the fabric than pinning, particularly on curved seams like necklines. Also, as long as you've knotted your threads properly, basting is more durable than pinning, as there are no pins to be accidentally pulled out or snagged on other items.

The basting line is mentioned again in the description as being a feature that will allow the garment to be "put together in a very brief space of time."

The description for the illustration calls this a "Work Bungalow" apron. "Bungalow Apron" is a bit of marketing term at a time when Sears Roebuck offered kits to build your own bungalow, then a great middle class aspiration. (1) The earliest reference I've found to the bungalow apron thus far dates to 1909, when it was described as becoming more popular than studio style aprons, though sewing patterns for studio aprons continue to be offered through the nineteen teens. (2)

Finally, the description notes that the garment in the illustration is made up in "checked gingham with trimmings of plain chambray."

In 1915, apron checks from the well-known Amoskeag mills could be purchased on sale for as little as 7 cents per yard. (3)

Beatrice (Nebraska) Daily Sun, Saturday, October 2, 1915, page 6

Assuming these checks were 36" wide, buying enough gingham for an apron would set you back 37 cents. The pattern retailed for 10 cents in stores, or for 12 cents if ordered by mail.

In December 1915, you could buy a Bungalow All-Over apron for 50 cents at the Chamberlain & Patterson Co. (4)

Natchez (Mississippi) Democrat, Sunday, December 12, 1915, page 5

If you were in Fresno, California, you could purchase an Amoskeag Gingham Bungalow Apron on sale for the very reasonable price of 29 cents (regularly 50 cents.) The kimono sleeves (cut in one with the body) indicate a simpler construction than the May Manton work apron with its set-in sleeves.

The Fresno (California) Morning Republican, Saturday, June 12, 1915, page 2

During 1915-1916 The periodical School Arts ("An illustrated publication for those interested in art and industrial work") ran a monthly feature profiling a selection of patterns that would appealing to (and suitable to) high school aged girls. This pattern was featured in the April 1916 issue as one of May Manton's "practical spring patterns."

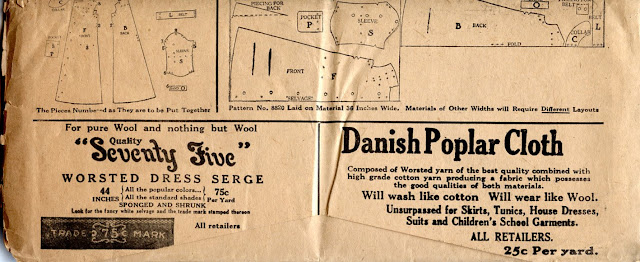

Layout is given for 36" wide fabric only. Note that provision has been made for piecing the back.

(1) If you watched the series Boardwalk Empire, you'll recall a bungalow kit home project gone horribly wrong.

(2) Even as late as the 1990s bungalow aprons were mentioned with humor or nostalgia as a quaint garment one's grandmother used to wear. "Like a pillow slip with sleeves" is a good description of a 1920s' bungalow apron.

(3) The New Hampshire Historical Society has masses of swatches from the Amoskeag Mills, but alas, they haven't been digitized yet.

(4) The Amoskeag checked aprons mentioned here are surely standard waist aprons.

.jpg)